[Note: This is a repost of our review from the New York Film Festival; we watched the film as intended at 120 frames-per-second, 4K resolution and 3D;?Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk?will play in Los Angeles and New York in one theater in each city on November 11th in120fps/4K/3D ?and wide on November 18th in traditional formats (24pfs/2D)]

120 frames-per-second in 4K high resolution and 3D might indeed be the future of cinema. Or it might?be a footnote curiosity of a brief but doomed method of telling cinematic stories, a la the sensory experiments with smell and seat shaking. Regardless, Ang Lee should be commended for having the bravery to attempt the medium first, particularly with a human drama. But Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk is problematic beyond the fact that the visuals look both crisp and fake; the story itself is too telegraphed, on the nose and rushed.

The novelty of extra-sharp visuals wears off by the time opening credits end and then, instead of being completely immersed in a new world, the sharpness opens up the film to many critiques that we wouldn’t have for a film with this level of budget and veteran actors. Because the resolution is so high and the frames are so fast, the sets all end up looking fake and you can feel almost all of the actors "acting." Watching this Halftime Walk is like having an extremely high definition look at the type of behind-the-scenes footage that would normally make you marvel at the final product because the costumes, sets and performances all look so staged from that vantage point. Except this is the final product. The normal polish that gives cinema a distinct look and feel is removed in favor of the longest video game introduction sequence ever made. It’s fitting that Lee has a football game as his backdrop and a brief sex scene in this film. Hi-res, many frames-per-second footage indeed might be the future method of watching sports and pornography, but for cinematic drama it’s (currently) nothing but a distraction for calling attention to how fake all the details are.

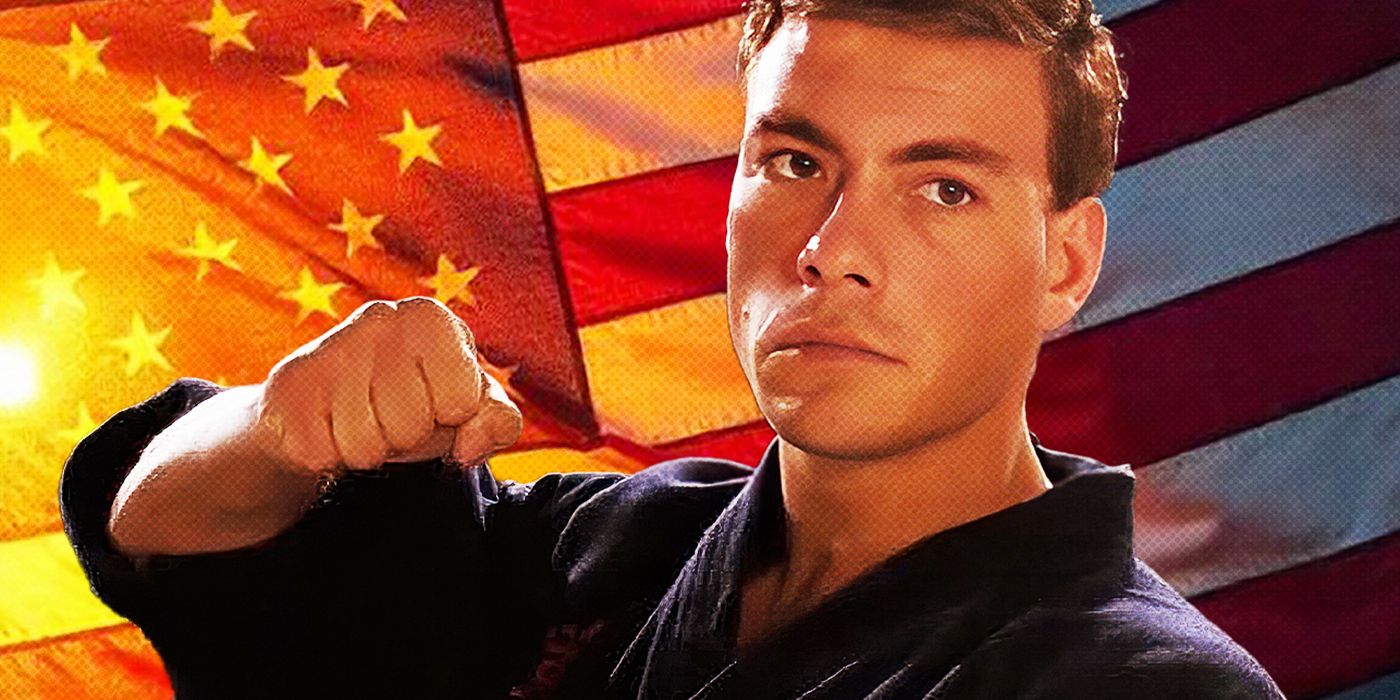

Billy Lynn tells the story of, you guessed it, Billy Lynn (Joe Alwyn). Lynn is a 19-year-old Iraq War hero, returning home to Texas for a special 2004 Thanksgiving halftime celebration at the Lone Star Stadium (née Dallas Cowboys; although the cheerleaders, blue star and Jerry Jones owner stand in are clearly the inspiration). Lynn is the quiet, emotional hero who’s wrestling with immense guilt for his inability to save his beloved lieutenant despite killing an insurgent up close and personal in an impersonal war; he’s contrasted by his troop of loudmouth young Bravos (Astro, Arturo Castro, Beau Knapp, Mason Lee) and his superior, a career soldier named Dime (Garrett Hedlund). Lee uses text messages from his anti-war sister, Kathryn (Kristen Stewart), the screams of fans and the smoky and loud theatrics of the Destiny’s Child halftime show to segue us back to Lynn’s first tour of Iraq in bursts of PTSD.

Halftime Walk is the story of a hero who doesn’t want to be a hero because everyone wants something from him in return; and that social currency comes from a day where he doesn't buy into his heroism. His sister wants him to talk to a psychologist so he doesn’t re-deploy. A cheerleader (Makenzie Leigh), who heavily flirts with him and protects him from all the extra spectacle noise of the day, wants him to remain a mystical hero (and thus, re-deploy). Dime wants him to become a career soldier. An agent (Chris Tucker) wants to sell the movie rights of his story to Hollywood, with Hilary Swank playing his role (in such a dated 2004 joke). And the Jerry Jones-type billionaire (Steve Martin) who’s invited the Bravos to this spectacle? He of course wants to display the myth of heroism to bring some pride to his 100,000 seat theater—and some extra enlistments in the US’s war on terror. The only person who didn’t want anything from Lynn other than a commitment to himself was the spiritually refined soldier he couldn’t save (Vin Diesel).

There’s a blueprint for a heady film about the various transactions of heroism and what the person on the other end of that exchange is getting in return. And also how an unpopular war can divide the populous into providing applause for everyone in uniform or viewing them as foolish for taking such an unprovoked risk. I can’t speak to how well the novel weaves these ideas, but these themes are not only telegraphed directly and lazily—they’re also sped through without any time to digest or ponder.

I’ve already mentioned how the frame rate and resolution are of a distractingly higher quality than the sets and images themselves—making everything look like a cheap playhouse—but they also turn many performances into cringe-worthy spectacles. Actors are not used to acting at this speed. And many of them, you can see them acting. It feels like watching forced cameos in a video game, extremely blocky and exaggerated.

There are a few exceptions. Stewart and Alwyn equip themselves quite nicely, but it’s worth noting that their performances are mostly reactionary and slower in delivery and dramatic thought process. If anything registers in this film from the imagery, it’s the pained tears of Stewart and Alwyn—their brother and sister bond is given the only extra definition and characterization in the movie. Diesel and Leigh also emerge unscathed from this Halftime Walk, but they’re both playing an obvious angelic and ethereal guise and are too good to be true (and introduced extremely quickly for the emotional output we’re supposed to receive from them). But Hedlund, Martin, all the Bravos (and their working class counterparts,?stadium security) and the distracting side profiles of women who are obviously not Beyonce, Michelle Williams?or Kelly Rowland all have moments of immense hindrance where we see them playing a part more than being a part. The same goes for the executive football suite, the halftime stage and the Iraq bunkers—the image looks so lifelike that the lives and places show their construction in ways we’re not used to seeing, except for maybe low budget religious films made for a quick buck.

In fact, the image (and sound) is so distracting and inviting of criticism, one has to wonder if it’d be better to watch not as presented at the premiere, but as a 2D, 60-frames per second (or lower) film (Note: 99% of theaters in the country cannot project 120 fps, so most will see the film in a lower frame rate closer to The Hobbit's HFR). I don’t want to pile on Billy Long with negativity and will give it a second chance in that medium, although I’m not sure that the pace of the narrative can be corrected to really register.

I applaud Lee for trying something new, attempting an entirely new medium, and for his openness—he wasn't sure how it’d turn out and he wants to learn from viewing this film and the response to it. But believe me, Billy Lynn’s Halftime Walk shows all the marks of a first draft. Nearly every part of the cast and crew has something to learn from Billy Lynn. In terms of the experiential new cinema, this feels doomed to footnote status. But bless Lee for trying.

Grade:?D+

Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk?will?Los Angeles and New York in one theater in each city on November 11th in120fps/4K/3D ?and goes wide on November 18th in traditional formats (24pfs/2D).